March 2, 2015

The Mouthpiece

The Humble Lion—Harold Johnson

By: George H. Hanson Jr., Esq.

John Harold Johnson was a lion— the King of the light-heavyweight jungle who sat majestically on his throne after his fists did all the roaring in the squared circle. And like light-heavyweight champion Battling Siki, who back in 1922 paraded his pet lion down the Champs-Élysées decked out in a tuxedo and top hat, Johnson owned one of these enormous cats.

According to his son Reverend John Roberts, or “Chuck” as he is called by family and friends, “Nobody was going to tell Harold Johnson that he couldn’t own one.” The church burst into laughter. Roberts further added, “We had to get rid of the lion because as it got bigger, it got hungrier” bringing more chuckles as he eulogized his father. Roberts stood tall and dauntless in the pulpit showing the strength and intestinal fortitude demonstrated by his dad throughout his life, especially during his eighty-seven professional fights.

Born on August 9, 1927 to the late Phillip and Catherine Johnson in the Manayunk section of Philadelphia, he was the second of three children. Johnson was a precocious athlete who excelled in gymnastics, swimming, and diving. He dropped out of high school; lied about his age joining the US Navy at the age of fifteen after convincing recruiters that he was three years older. It was during his enlistment that he discovered that he had a gift for the sweet science.

The program placed a two-minute time limit on each speaker. Charlie Sgrillo, President of the Veteran Boxers Association, walked briskly to the front of the church and administered the traditional ten-count for the fallen champion opening the floor. Philadelphia City Council President Darrell Clarke and Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell were first to mount the podium to pay tribute to the Hall of Fame champion and honor him with a proclamation from the City. “Pastor, we heard you, but two minutes is a difficult challenge for politicians” said Clarke, which had the church laughing. Blackwell added, “It is an honor to remember him.” The politicians understandably circumvented the time restrictions and paid heart-felt homage to one of Philly’s favorite sons.

The program placed a two-minute time limit on each speaker. Charlie Sgrillo, President of the Veteran Boxers Association, walked briskly to the front of the church and administered the traditional ten-count for the fallen champion opening the floor. Philadelphia City Council President Darrell Clarke and Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell were first to mount the podium to pay tribute to the Hall of Fame champion and honor him with a proclamation from the City. “Pastor, we heard you, but two minutes is a difficult challenge for politicians” said Clarke, which had the church laughing. Blackwell added, “It is an honor to remember him.” The politicians understandably circumvented the time restrictions and paid heart-felt homage to one of Philly’s favorite sons.

It was the late great Maya Angelou who said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Harold Johnson was a hero to the kids in his Manayunk neighborhood always doling out advice and boxing lessons at the North Light Boys Club. Joseph Mathis grew up in the area and was a member of the boys’ club. He made his way to the podium and opened with, “He is one of the all-time greats. He always had time for us.” The church chortled when Mathis added, “I was just a kid on the streets of Manayunk. He steered me in the right direction even though it took me a long time.” Mathis never forgot the indelible mark that Johnson left on his life and opened a living monument in his honor—the Harold Johnson’s Club—5822 Ridge Avenue, Philadelphia.

Johnson joined the punch-for-pay ranks after leaving the Navy. Over a quarter century (1946 – 1971) he compiled an impressive record of 76 wins – 11 losses – 0 draws – 32 kos including victories over boxing greats Ezzard Charles, the “Ole Mongoose” – Archie Moore and numerous top contenders of his era. He won the vacant light-heavyweight title on May 12, 1962 by a unanimous 15-round decision over Doug Jones. He would make one title defense before losing it by a controversial 15-round split-decision to Willie Pastrano on June 1, 1963. Many were convinced that Johnson was hoodwinked, bamboozled—a victim of larceny by two blind mice disguised as objective arbiters.

“He was my boyhood idol,” stated “Uncle Russell”—Hall of Fame promoter J. Russell Peltz. “Believe it or not I wanted to be light-heavyweight champion.” It was a little over three years ago that I listened as Peltz exploited his oratorical talent bringing the church to tears at “Bad” Bennie Briscoe’s funeral. He recounted the Philly legend with such vivid and colorful detail and anecdotes that I was prepared to become his agent on the lecture circuit. Thus, I leaned forward hanging onto his last word.

The ubiquitous and controversial Ken Hissner and I bookended former IBF junior-middleweight champion Buster “The Demon” Drayton in the next to last pew in the back of the church watching Peltz gain momentum. “When I was in high school, I would get my hair cut so short, just like Harold’s, that friends would yell ‘there goes Peltz with his Harold Johnson haircut!’”

The promoter disregarded the two-minute time limit for remarks and got in full stride like Smarty Jones at the one mile marker of the Kentucky Derby.

“I was the first person in the Arena when he fought Doug Jones!” Peltz detailed with humor his clandestine activities as a fifteen-year-old to not only buy a ticket but also attend the May 12, 1962 title fight between Johnson and Doug Jones at the Arena at 46th and Market Street. The future promoter’s mother had instructed him and his father to cease and desist from attending boxing matches since she was convinced it had a detrimental impact on Peltz’s upbringing. The teenager somehow managed to acquire the then princely sum of $10 for a top-priced ticket. On the night of the fight, he told his mom that he was going to a party at a friend’s house and hopped two buses and the Market Street elevated train to the Arena. You couldn’t keep him from witnessing his idol’s crowning moment.

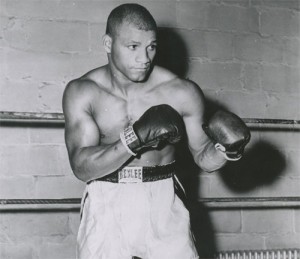

Standing a shade under six-feet tall, Harold Johnson had a body builder’s physique and could have easily graced the cover of Muscle & Fitness Magazine. Johnson was so well put together that the incomparable Angelo Dundee once quipped, “This guy had muscles in his toe nails.” But, unlike the overwhelming majority of muscle men, he moved with the grace and alacrity of a world-class ballerina using every inch of the squared circle jabbing, hooking, conducting traffic in the direction of his deadly right hand. “He was a slick, fancy fighter” commented Drayton earlier as we stood at the back of the church discussing Johnson, watching approximately 300 mourners take their seats.

Johnson was a dignified, spiritual, and humble man, a teetotaler who never smoked or uttered profanity. He downplayed his accomplishments. “The Man from Manayunk” opened speaker John DiSanto, whose website www.phillyboxinghistory.com is the cyber griot chronicling Philadelphia’s rich history of pugilism. “He was probably the most humble person that I have ever met.” DiSanto first saw Johnson at that memorable war of attrition between Mathew Saad Muhammad and Richie Kates at the Philadelphia Spectrum on February 10, 1978. Around 12 years ago he called up the former champion and paid him a visit. “You would never have guessed he accomplished so much. He was the most unassuming icon I ever met.”

Talent can be both a blessing and a curse. Johnson’s pugilistic prowess was so astounding that hardly any of the top light-heavyweight and heavyweight contenders or world champions wanted to share time and space in the ring with him. Joseph Mathis confessed that Johnson once told him “Rocky Marciano ducked me.” He had to fight Archie Moore five times—three consecutive times in a four-month span from September 1951- January 1952—to make any money. It was on December 10, 1951 that Johnson beat Moore by a unanimous 10-round decision—his sole win over the cagey and ageless wonder in five encounters.

Prior to the service, while hanging out at the back of the church I met Bill Nealon and his beautiful wife Nancy. Nealon, a professor at Philadelphia University, recounted how his father Judge William Nealon—appointed by JFK in 1962 and presently the longest serving federal jurist in the 3rd circuit in our nation’s history—met the light-heavyweight champion. After stopping Tommy Merrill in the ninth round of a non-title bout on March 19, 1963 at the Catholic Youth Center in Scranton, PA the elder Nealon approached Johnson for an autograph. He asked Johnson, “Would you write to Bobby, Billy, and Jackie and then autograph?” Nealon wanted the champ’s John Hancock for his three sons.

Despite Skinny Davidson, Johnson’s trainer, instructing him to just sign his name, the champion was gracious and took the time writing the autograph as requested. Johnson would have his title “stolen” by the judges less than three month later on June 1, 1963 in that fateful match against Willie Pastrano. According to Peltz it was a “despicable decision” that he believes “ranks among the 10 worst in boxing history.”

Nealon, professional boxing judge with the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission from 1989 – 2012 has been at ringside for bouts featuring Bernard Hopkins, Nate Miller, Dwight Muhammad Qawi, Charles Brewer., James Toney and Buster Mathis Jr. He relayed his father’s story to Johnson’s children six years ago. They allowed him to see the former champion at the Delaware Valley Veteran’s Home where he had been admitted since 2007. In Nealon’s estimate he has visited Johnson at least one hundred times.

The former arbiter of professional pugilism adds, “Harold Johnson was more than a champ. He was a kind and humble man who could never say no. He was my boyhood hero. He’s still my hero. The man called ‘Hercules’ had the most perfectly cut body and heart of gold.”

Funerals are truly for the living and not for the dead. I learned more about Johnson than I had discovered as an aspiring 13-year-old boxer in Sam Andre and Nat Fleischer’s, “A Pictorial History of Boxing.” I had no idea that Johnson was an excellent drummer—a trait that has been passed on to his grandson John Jr. who works for 25-time Grammy winner—Stevie Wonder. The book never mentioned that the champ loved fancy cars. It was Pennsylvania State Athletic commissioner Rudy Battle who had everyone laughing with; “Harold and I developed a friendship through a neighbor whenever Harold and his automobile were visiting the neighborhood.”

Johnson had many titles, Navy veteran, world champion boxer, Hall of Famer, drummer, and father. But, to Charlotte White, his only remaining sibling, he was her big brother and protector. Her voice reflected the loss of the man “who took me to the movies when I was three-years-old.” “He carried me on his shoulders upstairs because we couldn’t sit downstairs”—reminding us that it wasn’t too long ago that racial segregation was common practice and oftentimes the law. “Harold made sure nobody bothered his little sister.”

Those who were away on business including Bernard “The Alien” Hopkins paid their respects by calling Johnson’s family to offer their condolences. Many came to say goodbye to the great Harold Johnson. Also in attendance were two former world boxing champions—The Honorable Judge Jacqui Frazier-Lyde and Nate “Mr.” Miller; Marvin “Machine Gun” Garris, Bozy Ennis, Joey Eye, Timmy Sinese, Zack Pomillo, Tony Borrelli, and Tony Burwell. They all made the trip to North Philadelphia’s Shiloh Apostolic Temple a half block behind The Legendary Blue Horizon to celebrate the life and legacy of the “Man from Manayunk.”

There is an old adage that death occurs when a person is forgotten—never mentioned—forever absent from the tongues of the living. Harold Johnson didn’t die on February 19th; he merely transitioned to another realm. As long as there is life on earth, Harold Johnson will live forever, in our hearts, in our minds, and in our stories. Hopefully, if you have read this far you grasp why he meant so much to all of us.

There is an old adage that death occurs when a person is forgotten—never mentioned—forever absent from the tongues of the living. Harold Johnson didn’t die on February 19th; he merely transitioned to another realm. As long as there is life on earth, Harold Johnson will live forever, in our hearts, in our minds, and in our stories. Hopefully, if you have read this far you grasp why he meant so much to all of us.

Rest in peace, Champ. You will always be our hero.

Continue to support the sweet science, and remember, always carry your mouthpiece!

ghanson3@hotmail.com